How To Regulate A Politically Charged Bookstore

The content we read influences the decisions we make. Or do the decisions we make influence the content we read?

The content we read influences the decisions we make.

Or do the decisions we make influence the content we read?

Social media regulation may be the most polarizing topic of the last decade. Despite countless hearings, public debates, and tragedies - almost no change has gone into effect.

Comparing technological disruption to its analog parallel in the physical world can often help build intuition around its causes and effects.

For the purpose of this post, I’d like to run a thought experiment about a book store.

Specifically, our goal is to understand how content curation affects the overall production of content, customer experience, and the opinions of a society that gets its information primarily from books in a pre-Internet era.

After considering the positive and negative effects of book curation, our goal should be to design regulation (if even necessary) to maximize the positive and minimize the negative.

The Effects of Curation on Content Diversity

Imagine you are a book enthusiast shopping for a new novel prior to the arrival of the internet. You walk into a book store and find thousands of books scattered around the shelves. All around you are books covering a diverse set of content across topics, perspectives and languages.

Because of the sheer breadth of content, browsing the trove of books in a random order and picking the one that best catches your eye is unlikely to yield a book that’s very satisfying to you.

You may not realize that your satisfaction with this experience is quite low because it’s the best option you have. Notably, there are many implicit factors that guide your book decision. For example, you’re much more likely to choose books that are near the front of the store, or on shelfs that are eye level, etc. While the book store owner may not realize this, they are implicitly curating the books in the store by choosing which books are positioned where in the store. Regardless of the intention, this implicit curation has a big effect on the book you choose to buy. Let’s call this random curation.

To improve your shopping experience, the book store owner soon decides to place two tables in the front of the store - one for the best non-fiction books and one for the best fiction books. How do they choose which are the “best” books to feature in the front of the store? Well they may choose ones that are their personal favorites, ones that their friends recommended to them, ones that are vetted from some third party source that they trust, or simply the ones that have the best sales.

Now that there are book recommendations in the front of the store, you find that you’re much more likely to browse those first. Let’s call the role that the book store plays in this new paradigm centralized curation.

Having this explicit curation makes shopping for books 10x easier for customers since they no longer have to browse through a completely random assortment of books. Soon every other book store in the city follows this curation model.

Unfortunately, some problems have been created with this paradigm shift.

In fact, this decision has completely disrupted the competition between producers of books. Now it is crucial that they get featured on one of the first two tables in the book store, assuming they want to continue making a living selling books. This is because the books that are featured have an exponentially higher reach to customers than the books buried in the back of the store.

Because of the role centralized curation plays on book sales, it is in the publishers’ incentive to publish content that book store owners will want to feature on their front tables. That is to say, convincing the book owner to read and like your book is an important proxy for selling to end customers. As a result, publishers skew their content to the interest of the book store owners.

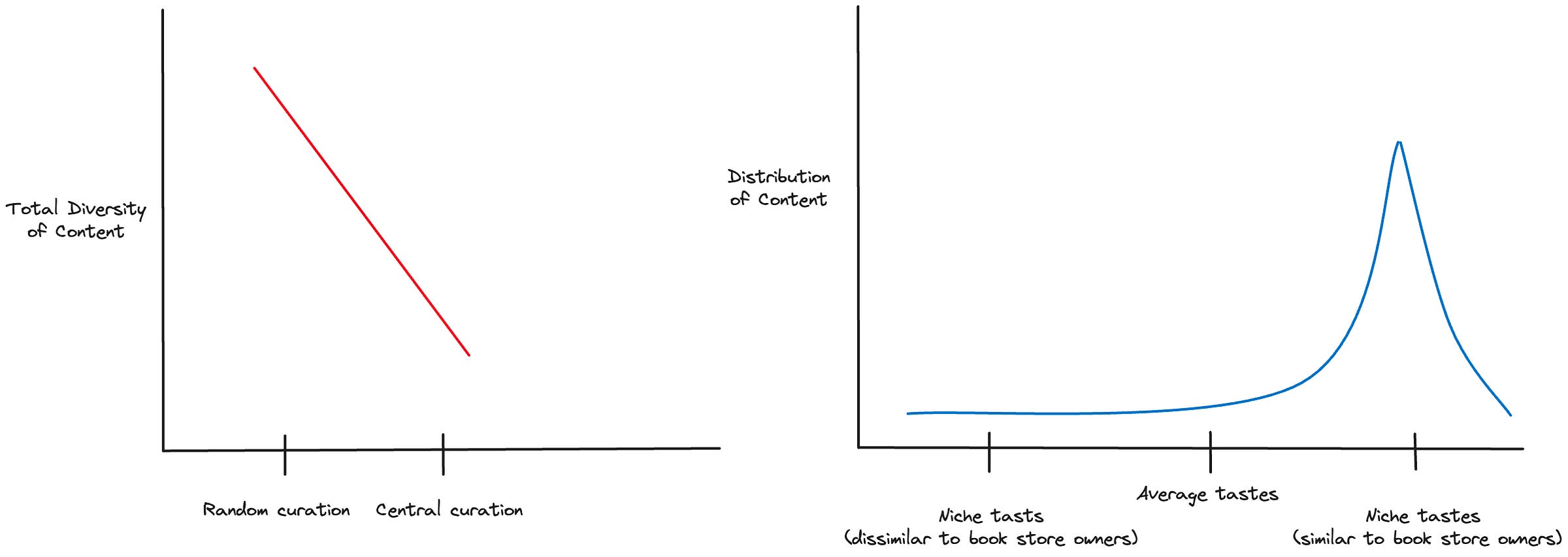

Book store owners probably share a lot of common traits. For starters, they must have enough money to actually own a book store, they’re probably more educated and older than the average member of society, etc. Because this limits the audience that authors create content for, the diversity of content dramatically shrinks.

Book stores love this model because it gives them power as a central curator. They get to be in charge of what content people see and how it is delivered. Since they skew the distribution of content, their opinions get an outsized effect on the opinions of society.

However, soon a new book store enters the market and in order to make a name for themselves, they introduce a new approach.

Instead of having a set of tables in the front of their book store, they hire an enormous staff to give customers one on one attention as they shop for books.

When the customer first walks in, they’re assigned a staff member who first runs a quick exercise to learn about their preferences. They show them a series of commonly known books and ask the customer which ones they like.

From this survey, they learn their customers’ tastes and can now walk them around the book store giving specific recommendations on books they may like next. Over time the staff reps get better and better at their jobs and customers find so many books that they like and buy. Since user’s interests are governing the distribution of books, let’s call this decentralized curation.

Unsurprisingly, with this white glove service customers are more likely to find specific books that match their interests as opposed to settling for the mainstream best sellers in the front of the store.

Suddenly, the competitive landscape for book owners has radically shifted again. Now, instead of catering towards a small set of book store owners, they must write books that appeal to readers. In this model, the diversity of content explodes since there are many more niches that are now possible to sell to.

The Effects of Content Production on Consumption Habits

It’s clear to us now how curation effects the production of books.

Centralized curation leads to a less diverse, more concentrated set of content that favors the centralized curator. Decentralized curation leads to a more evenly distributed, diverse set of content that favors the interests of society.

Centralized curation places a bottleneck on content production, creating a filter that tends to favor the opinions of a wealthier, older, more elite demographic.

Of course, this is not universally true (even within book store owners, there is some diversity to be sure), but at the aggregate level this is the trend that we’d expect.

The positives of this is that we’re much less likely to surface extreme content to customers. It’s still there mind you, but it’s buried in the back of the book store where you’re less likely to stumble upon it. In fact, you would probably only stumble upon it by random chance or if you were specifically looking for it.

In the decentralized curation paradigm, you are likely to find the content that best matches your interests. This means that many niches can form around content that isn’t mainstream. As it turns out, this has the benefit of creating many unique, dynamic sub-cultures. This also creates a more fair and competitive market for content producers, where they can avoid catering to a middle man and build for their audiences directly.

On the aggregate level, we see distribution skew to the average interest, with more content at the ends. Having once lived in a world of centralized curation, the book store owner will now quickly notice how the average content that is being produced is skewing away from their interests.

And of course, the problem occurs most pointedly at the extremes.

The Effects of our Moral Priorities on Regulating the Bookstore

I think it’s fair to say that most people would find it preposterous to ban book stores from giving customers white glove, personalized service.

If I walk into a book store and tell a staff member that I like reading science fiction, particularly political dystopian works, I would very much appreciate a recommendation of other similar books. That’s a much better experience than aimlessly wandering around a book store hoping that I stumble upon a similar book.

But let’s say I’m not feeling the particular recommendation today and I ask for more. The staff member may recommend a few more sci-fi books until he quickly realizes I’m not in the mood for sci-fi at all. He begins to rotate between a few other topics, and in the midst throws in a few edgy examples to get more data on what I’m looking for.

One of these recommendations is a politically charged book that makes arguments for perspectives that I normally do not adhere to. Yet out of curiosity, I decide to choose this book today.

Even without knowing how I responded to this book, we have an interesting moral dilemma. Who do we decide is responsible for me reading this politically charged book today?

We could attribute responsibility to the author of this book for producing it in the first place. We could attribute it to the staff member for including it in his recommendations. Or we could attribute it to me for deciding to buy and read it.

Let’s call the first a supply-side argument, the second a curation argument, and the third a demand-side argument.

How do we approach each of these categorizations and what does it tell us about our moral values?

Supply-side Argument: We believe that content of this form shouldn’t be produced in the first place. We believe that the moral values we have are objective truths and that anything counter to those pose a risk to society. We may loosely believe in freedom of speech, but not when it conflicts with our moral truths.

Curation Argument: We believe that while everyone has a right to produce whatever content they want, we should restrict the distribution of this to customers. Particularly, we do not trust the discretion of the book store staff members, as they have their own self-interests in mind. Particularly, they want to give customers content that is more likely to get them to return to our bookstore.

Demand-side Argument: We believe that individual customers are responsible for their decisions on which content they consume. We recognize that curation decisions have the ability to sway content choices, but we believe that there is sufficient diversity with which customers can still make good and bad choices. And of course, customers still have the discretion to choose whether to believe and trust the content they read.

I like to think that few people would believe we should regulate book stores by prohibiting authors from creating books on certain topics at all. And even if you did believe this, you would need to have a non government entity enforce it to avoid violating freedom of speech laws. So it is the least practical solution.

Many who consider this scenario a serious problem would make the curation argument. They will argue for “freedom of speech, but not freedom of reach”. If we go this path, we have to choose one of the three curation strategies over the others.

I think it would be silly to tell bookstores that they all have to go back to a system of random curation. This would be a net negative for customer satisfaction and would shrink book sales all together. All three parties would be angry: publishers, book stores, and customers.

If we choose to lean on a system of centralized curation, then we believe that we should entrust content choices to the moral discretion of the book store owners. This means a concentrated, fairly homogenous group of people would get to skew the distribution of content production. Recall, this is independent of the choices of customers because content producers are incentivized themselves to produce more homogenous content.

It would mean less diverse content overall, leaving customers fewer choices entirely for finding content they like. And of course, the curation choices that are made will naturally still be in the best interest of the book store owner, albeit they will have less ability to target their reach to customers individually.

I like to think that most people still believe in having a diverse set of content and the rich, dynamic sub-cultures that it creates. Again, it is simply the extremes we argue about.

We could solve the extremes by banning book stores from allowing staff members to give personalized advice to customers entirely. We could argue that instead, customers must be forced to walk down the shelves chronologically in order to give a fair chance to all content. This seems ridiculous. As ridiculous as banning waiters from asking their customers if they like sour or sweet drinks and providing menu recommendations using that data.

So instead, we could ban recommending only the “extreme” content, which then requires a moral determination on what is considered extreme and what isn’t. And then training every book store staff member in the world on the distinctions and enforcing their behavior. Enforcement would mean holding book stores and their staff members liable for recommending any book that skirts the moral line that we created. Given the vast amount of books in the catalogue (and the infeasibility to read and understand them all), this would scare book stores to the point that they would have no choice but to go back to random or centralized curation - or shut down entirely.

And that would simply return us back to the situation of centralized curation. In the mean time we would tussle over trying to choose a universally acceptable moral line in a society that prides itself on diversity of moral opinion.

Finally, a more nuanced opinion might be to simply limit the specific data elements or amount of data that the staff members are allowed to use for their recommendations. This way their recommendations could still be personalized but not hyper-personalized. We may choose to block collection of data on protected classes, like race, gender, socioeconomic status, etc.

This sounds pretty reasonable on the surface. And in order to avoid conflict, we might suggest data categories that are attributed to the customer and not the book. For example, it’s easier to say that we can’t use the race of the customer to suggest content, rather than saying we can’t the property that a book covers racial topics.

Unfortunately, because of this fact, our policy is unlikely to solve the problem at hand. That’s because the topics we enjoy consuming have strong correlations with our personal attributes. If I’m reading content in English, I’m more likely to be from the US than China. If I’m reading content about sports and science fiction, I’m more likely to be male than female. If I’m reading nonfiction content about economics and philosophy, I’m more likely to have a college degree. I want to be clear, this isn’t a prescription of how things should be, it’s just a reflection of the state of society today. It’s also not universally true, only on the aggregate. Of course there are tons of exceptions and counter examples to these correlations, but that doesn’t defy the correlation all together.

So this means that properties of content embed a lot of information about properties of the customer. It would still be wise to regulate the use of personal attributes for personalization for privacy sake, but we can’t expect it to solve the problem.

So if we’re looking for a more ideal solution, we’re left with only the demand side argument.

What Would Demand Side Regulation Look Like?

If we blatantly assume that customers are responsible for their own decisions on which books to consume, we ignore all of the nuance around the effect of curation.

Curation does impact content choices. The entire first half of this post is dedicated towards understanding those impacts. The role of curation is to embed convenience in the choices of customers. To efficiently guide them towards content that they will like, minimizing time spent searching and maximizing time spent reading.

With decentralized curation, we create the best environment for individual accountability. That is, we have a vast, diverse set of content that is tailored by publishers for the tastes of consumers, without outsized impact of the preferences of bookstore owners. But we leave room for “bad” curation decisions. That is, curation decisions that in the best case, are ignorant to the underlying content, and in the worst case, are made with malicious intent. Curation decisions that result in the distribution of extreme, morally ambiguous content.

It is perfectly acceptable for an individual to willingly choose to read any content that they wish. It is the “ill intent” of the curation decision, mixed with a reasonable sounding excuse to make the curation decision (i.e. “personalization), that gives us pause.

The demand side answer on how to solve this problem is to maximize customer choice. If the goal of curation is to add convenience to the customer decision, then we must make it equally convenient to change the curator.

I choose which bookstore I shop at, which means I implicitly choose the staff that gives me recommendations on which books to consume. While the staff may guide me most of the time towards content I like, they may also guide me towards content that is questionable. Again, their reasons for doing so might be 1) ignorance or 2) malicious, self-serving intent.

When I start receiving these questionable recommendations, I can respond in two ways. I can either continue to shop at this book store, which means I’m satisfied with the content that I’m receiving. This is within my right and I should be held accountable for the decision that I make. We could argue that the content I’m seeing is “brainwashing” me into staying, but this, in my opinion, is belittling the autonomy of the customer to choose what content he/she finds compelling and not compelling. The way to fix this problem is to fight bad content with good content. To fight disinformation with education.

On the other hand, if I truly believe that the personalization decisions that I’m receiving are bad, then I have the ability to walk down the street and take my business to a competing book store. That is the fundamental essence of a free market economy.

The catch is that if I do so, I will be greeted with a book store and staff that is not well versed in my preferences. We will have to start from scratch. Which means the first few times I frequent this competitor, I will not find content that is as good as the content I received at the previous book store. If this is a new bookstore, then it is also likely that they will have fewer selections than the previous book store, since they are newer and haven’t had as much time to build up their book catalogue.

This is the ultimate problem with regulating the book store. It’s not a matter of controlling which books are on the shelves, or which books the staff recommends, but controlling how convenient it is for me to switch to a different book store. This is the dynamic that allows bookstores to serve their own self interest instead of mine. Or if we’re giving them the benefit of the doubt, to get away with simply poorly made and ignorant personalization decisions. In a perfectly competitive market, there is little room outside of serving the customer’s best interest.

To make the market place more competitive, we would need to disable two network effects inherent in the book store economic model by

Enabling easy access to large content catalogues

Allowing easy exchange and modification of personalization data

Since all books share a unique identifier, we could create a master database of all books and allow book stores to subscribe to that database. This will allow book stores to recommend any book from that database. We could then create an easy interface for publishers to distribute their books to any store.

Since we have a central database of content, we could require book stores to maintain a written record of your previous content decisions. In fact they almost certainly have this written somewhere anyways in order to keep providing you with recommendations. So we really just need to standardize the format. Once we do this, we could give the customer the the right to take their historical data with them to a competitor.

In a more competitive market, we would see many different curation strategies instead of a single, universal one. One may veer towards the center while one may veer towards the extremes. The beauty of this is that we don’t no longer have to place the burden on the curator, rather we place the burden on the customer to make the decision that is right for them. To influence change, rather than influence government or book store owners themselves, we must influence our fellow book readers directly.

Counter Arguments and Closing Thoughts

In reading this, you may have found yourself disagreeing with a few things. Here are some of the ones that I’d expect

The moral line that the extreme “bad” content crosses is not that blurry. In fact, is quite obvious that we should not have content that incites violence, or claims racial superiority, or states inaccuracies. These are objectively bad.

Consumers can’t tell that they are being lied to, or that the curators are acting with ill intent. It is the job of regulation to protect the end user.

How does this apply to children? Children are particularly vulnerable to poor curation choices and are not old enough where it is reasonable to hold them accountable for their own decisions.

These are my responses to those objections.

The fact that someone disagrees that this is bad content (e.g. the one who produced it and the one who reads and agrees with it) means it cannot be an objective moral truth. It is likely a moral objective truth with respect to a single community but not universally. It is within the right of any individual to believe what they want to believe, even if it disagrees with the moral framework of others. If someone wants to convince someone else that their framework is better, then the responsibility is on former person to construct an argument that wins over the latter.

I think this idea belittles the intellect of the consumer. If consumers can’t tell the difference between fact and falsehood, or judge the intent of those they interact with, then this is an education problem not a personalized curation problem. We should spend our time and energy making sure that all members of society are in a position to judge the quality of content for themselves.

I would agree. For children specifically, I believe that a centralized curation approach is best. In this case, we would disallow white glove, personalized recommendation service to people under the age of 18.

A democratic system is built on trust in one another. The role of regulation should be to maximize choice so that we can place the most accountability on the individual and not intermediate institutions. By doing this, we’re placed in direct association with fell members of society. Rather than blame a middle man, we blame ourselves. That can be scary because it means that these problems are our fault. Or it can be uplifting since it means we have the power to solve it ourselves.